Moving on then from buildings, we return to the developing liturgical and ecclesiological tradition at Shepherds Law. Again, Harold’s own words may set the scene here. He writes:

‘But the most important revelations which life at Shepherds Law brought were not at all first perceived and understood. After some months I began to feel uncomfortable. Then I understood it as follows: I was in a cardboard box with SSF written on the outside of it. But the bottom of the box had just given way and I was in free fall. I came to see it as akin to Lewis Carroll’s Alice falling down the rabbit hole; but what I landed in was an awareness of communion with the monastic saints of Northumberland who had lived a similar life in the centuries before the Reformation and the Dissolution of the Monasteries.’

This led to a reinterpretation of Harold’s position. In pursuit of this he gained permission from the Minister Provincial of the Society of St Francis to approach Quarr Abbey on the Isle of Wight to see how the concept of stability and communion with a local tradition and the monastic way of life had been contextualized there. Quarr, a Benedictine monastery within the Solesmes congregation, had been the place of exile of the French community early in the twentieth century; it had thus not been involved in the controversies following the English Reformation. The then Abbot, Dom Aelred Sillen, welcomed this initiative and Harold lived at Quarr for a number of weeks learning from community life and from the Abbot himself. The large library there was also a key resource. Alongside this stood a discipline whereby Harold attended the local Anglican parish church of Holy Cross, Binsted on Sundays and major holy days.

At the inception of Shepherds Law Harold had been given permission by the SSF Chapter to evolve a specific liturgy as appropriate. From the contextualized experience at Quarr (further visits followed) and the discipline of daily attendance at the Liturgy, the Opus Dei, arose the move towards using forms of prayer used by the monks of Durham to celebrate the festivals of St Cuthbert, their patron. Through study of the monastic liturgical literature at Durham, in the British Museum, and at the Scottish National Library in Edinburgh, Harold began to gather together both the words and the musical texts which now underpin the rich and sometimes complex liturgical diet used daily and weekly at Shepherds Law. The bringing together of this material has itself been an extraordinary and unique achievement. This also stands behind the patronage of the hermitage which is dedicated to St Mary and St Cuthbert.

The other key development which arose from Brother Harold’s time at Quarr and indeed through his other travels and encounters was an ever-increasing and deeper understanding of the mystery of the Church and of Christ’s prayer for the Church ‘that it may be one that the world might believe’. Shepherds Law was becoming a meeting place for Anglicans, Roman Catholics and Orthodox; Methodists and other free-church men and women also had links. The hermitage was thus becoming something of an ecumenical centre in microcosm. It was, as Harold puts it himself: ‘a neutral ground on which it was possible to appreciate spiritual treasures which normally lay beyond the boundaries of the separate denominations’.

Throughout this time too, Harold’s links with the Community of Transfiguration at Roslin in Edinburgh, and particularly with Father Roland Walls, were also formative. This community had been founded by Roland Walls as an ecumenical religious initiative and included Anglicans, a Presbyterian minister, and Roland himself, an Anglican priest who would eventually become a Roman Catholic. The community’s buildings were based in a former miners’ institute in the humblest of buildings often described by visitors as ‘glorified chicken huts’! Each of these different experiences and influences eventually persuaded Harold that the faith within him was, as he puts it himself, that of the ‘undivided Church’. Harold notes:

‘Without denying my upbringing, which had been begun by my Nonconformist grandfather telling me stories from John Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress, or what I had subsequently received from the Society of St Francis, in 1996 I asked the Bishop of Hexham and Newcastle for the communion of the Catholic Church.’

This move was accomplished while still allowing Harold to live at Shepherds Law and indeed to continue to use the Anglican forms of the monastic tradition. The service of reception witnessed to a continuity of life at the hermitage. All such moves, of course, will be more difficult for some to accept than others, but overall the diaspora and local communities associated with Shepherds Law, Anglican, Roman Catholic and otherwise, have continued and indeed grown. The links with St Mary’s Roman Catholic church at Whittingham have broadened local Roman Catholic support for Harold, and at least one of the trustees is, by coincidence, a Roman Catholic and another by nurture a Presbyterian. In contemporary language, then, Shepherds Law has become a place of Receptive Ecumenism, that is, somewhere where people of different churches can encounter and be enriched by traditions not present within their own communities.

Perhaps most precious in this are the monastic traditions and within that, elements of the eremitic life. In all this, however, while treasuring most fondly the historic patterns of prayer and the contemplative life, Shepherds Law still points forward both to new and richer understandings of the monastic tradition and indeed to the ‘coming great Church’, when ‘all shall be one that the world may believe’.

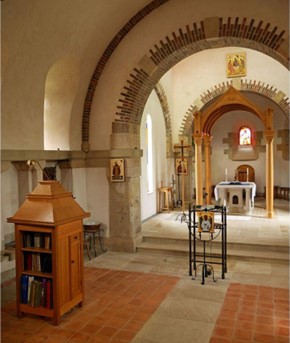

On the practical level, there are still things to be achieved. We have already noted that some aspects of the chapel remain unfinished. Then, also, the library is at present packed into too small a space for the number of books which have acceded to it. There is space to build a guest house for those who visit, and there are continuing practical needs such as a covered link to the church, space for a workshop and the like. The Friends of Shepherds Law are a key support and funds were raised to install a gas fuelled kitchen stove and some electric lighting. Alongside the solar panels, another supporter of Harold has contributed by supplying a diesel electric generator. On the human level, Harold continued to pray that one or two others might join him in this community eremitic life which he has pioneered.

(An extract from Oneness: the Dynamics of Monasticism, ed. S.Platten, Canterbury Press 2017, Chapter 4 by Stephen Platten, © The Contributors 2017)